What is a User Interface of Unknown Provenance? And what exactly is the User Interface of Unknown Provenance process (UOUP for short)? When are you authorized to use this process? What does this process look like in detail?

We answer these questions and dive deep into IEC 62366-1 in this article to show you step by step how the User Interface of Unknown Provenance process works.

What is a User Interface of Unknown Provenance?

Let’s first take a look at what a User Interface of Unknown Provenance is. IEC 62366-1 defines it as follows:

“User interface or part of a user interface of a medical device previously developed for which adequate records of the usability engineering process of this standard are not available.” (Source: IEC 62366-1:2021-08; 3.15)

This refers to user interfaces that have already been approved but were launched on the market before the introduction of the 2015 standard and therefore do not have IEC 62366-1-compliant documentation. These user interfaces are therefore of unknown provenance in relation to the usability engineering process according to IEC 62366-1.

What exactly is the User Interface of Unknown Provenance process?

The UOUP process is an abbreviated alternative to the full usability engineering process. The goal of the User Interface of Unknown Provenance process is to evaluate these user interfaces of unknown provenance and prove that they meet the requirements of the standard. This should be done as effectively as possible.

The process relies on existing documentation wherever possible. This documentation may, for example, have been created during the development process or in the course of post-market surveillance. It enables you to deliver a complete documentation of usability related risks without having to go through the complete usability engineering process for existing user interfaces.

You can find the User Interface of Unknown Provenance process in Annex C of IEC 62366-1: “Evaluation of a User Interface of Unknown Provenance”.

Under what scenarios can I use the User Interface of Unknown Provenance process?

IEC 62366-1 precedes the UOUP process with four examples to show who is authorized to go through this process.

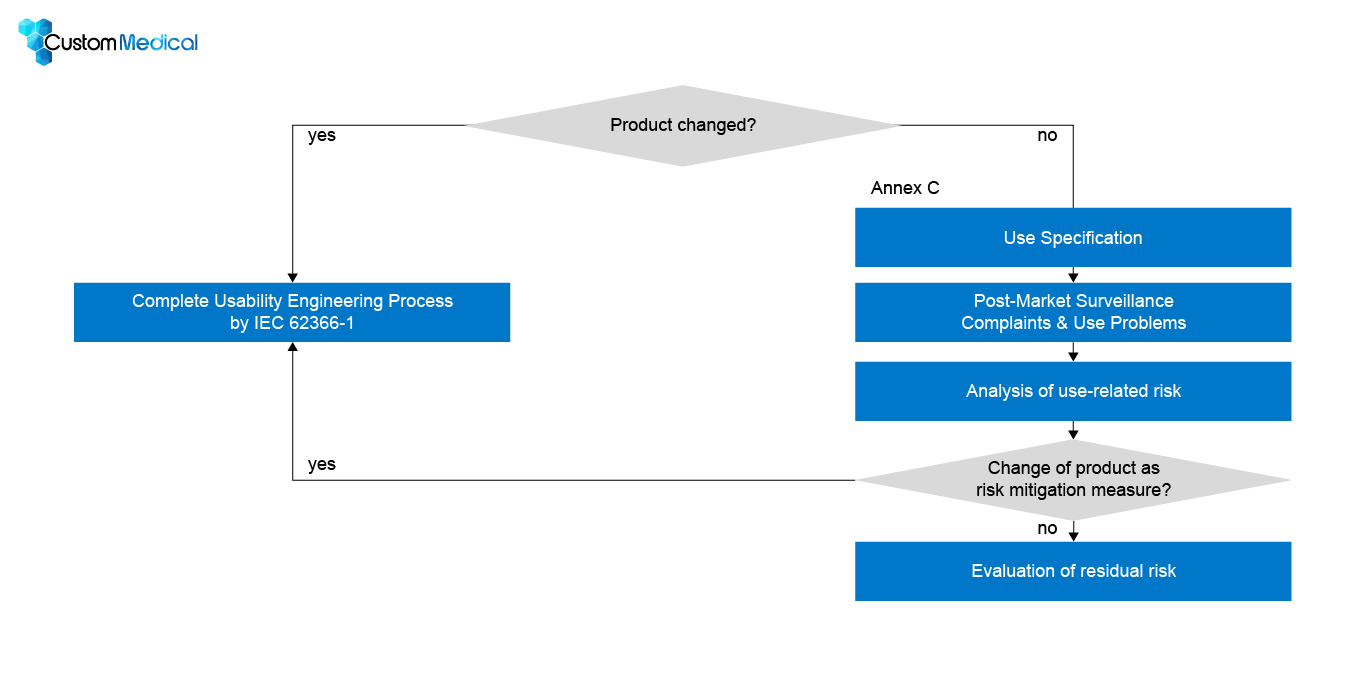

Example 1: Here, an unchanged and already existing user interface is given, which is to be evaluated by the UOUP process. The aim is to determine compliance with IEC 62366-1 for this existing user interface.

Example 2: Example 2 deals with the scenario of a user interface without adequate documentation according to IEC 62366-1, which is partially modified. Here, the modified user interface must go through the entire usability engineering process. The unchanged parts of the product can be evaluated with the shortened UOUP process.

Example 3: The third example is about a user interface that was developed before the introduction of IEC 62366-1:2015 and that gets a new software feature. Here, the user interface of the added feature and all parts affected by the added feature have to go through the complete usability engineering process, while the unchanged rest of the product can be evaluated through the UOUP process.

Example 4: This is about an existing user interface that is modified to rely on a universally usable component. This could be a computer mouse, for example. This general-purpose component does not have sufficient documentation for its development. If changes to the user interface are now necessary to integrate this component into the product, all changed parts of the user interface must go through the entire usability engineering process, while the unchanged parts are allowed to go through the User Interface of Unknown Provenance process to determine compliance with IEC 62366-1.

These four examples make the principle clear: Parts of a user interface that are changed are no longer “of unknown provenance” and are therefore required to go through the complete usability engineering process.

Unchanged parts of an existing user interface may be evaluated with the shortened process in order to prove compliance with the standard as time-saving and efficient as possible.

This classification makes sense, after all, you are currently working out what the new user interface should look like. This gives you another chance to apply the usability engineering process to the newly developed parts.

In the following, we will explain the UOUP process step by step.

Step 1: Use Specification:

Here you will be prompted to create a Use Specification for your medical device. This is no different from the normal usability engineering process.

It must contain:

- The Intended Medical Indication: They therefore define what the medical device is to be used for. A clear exclusion can also be defined here (i.e. a statement about what the medical device must not be used for).

- The Intended Patient Population: You define on whom the medical device is to be used. The patient groups must also be described in the relevant criteria. For example, health status and age are mentioned.

- The Intended part of the body or type of tissue applied to or interacted with: Here you record the body part or type of tissue where the medical device is to be used.

- The Intended User Profile: Here you define by whom the product is to be used. Each user group must be described in the relevant criteria.

- The Intended Use Environment: This is about the context of use in which the medical device is to be used. Here, too, you must define the relevant criteria. So how is your use environment to be defined?

- The Operating Principle: How does the medical device operate? How does it achieve its effectiveness?

If you do not yet have a Use Specification, you can use your supporting documentation (such as your Instructions for Use) and your Technical Documentation to derive the Use Specification based on them.

Step 2: Review of post-production information

Step 2 requires the following from you:

- You must review your Post Market Surveillance data (including complaints and reports of incidents and near misses, as well as CAPAs implemented based on identified issues and complaints) for instances where a Use Error may result in a hazard or hazardous situation. (source: IEC 62366-1:2021-08; C2.2)

- Any cases where the available data suggest a hazard or hazardous situation due to poor usability must also be identified. (source: IEC 62366-1:2021-08; C2.2)

- All these cases must be documented in the usability engineering file. (source: IEC 62366-1:2021-08; C2.2)

So, you check whether there were any errors, use problems, hazards or misunderstandings on the part of the users and what risk is associated with the respective error.

The cases recorded here in the usability engineering file must then be dealt with in steps 3 and 4. (source: IEC 62366-1:2021-08; C2.2)

Step 3: Hazards and hazardous situations related to usability

The goal of step 3 is for you to ensure that “hazards and hazardous situations related to usability” (source: IEC 62366-1:2021-08; C2.3) are identified and documented! You now define the cases that are relevant for risk control in step 4.

Now you turn your attention to the data of the already existing risk analysis of your product. The hazards and hazardous situations identified here are checked and compared with the PMS data. In addition, you look to see whether new hazards and hazardous situations have arisen in the PMS data in connection with usability. You then document these in your usability engineering file.

Step 4: Risk control

Now, for all hazards identified in step 3, it is necessary to check whether risk control measures have been implemented and whether they have been reduced to an acceptable level. If the risk assessment showed that risks are acceptable, no measures need to be implemented. If the risks are not acceptable, it must be ensured that “adequate risk control measures have been implemented and that all risks are reduced to an acceptable level as indicated by the risk assessment” (source: IEC 62366-1:2021-08; C2.4).

It is important to note that normally these risk control measures already exist for the existing product. If no measure exists for a “critical” risk, it must be introduced.

If, in the course of this risk control, changes have to be made to the user interface, then it has to go through the complete usability engineering process and is no longer considered to be “of unknown provenance”.

To ensure that only an acceptable residual risk remains, you then perform step 5.

Step 5: Residual risk evaluation

Now you are required to re-evaluate the overall residual risk according to ISO 14971:2022, considering the knowledge gained in steps 3 and 4 (source: IEC 62366-1:2021-08; C2.4). If the residual risk is acceptable, your product has successfully passed the UOUP process!

Conclusion

The User Interface of Unknown Provenance process allows you to demonstrate compliance with IEC 62366-1 as efficiently as possible for user interfaces or parts of user interfaces that were developed before the introduction of the 2015 standard and thus without the usability engineering process. The focus here is on discovering and controlling all usability-relevant security risks. This is done on the basis of existing documentation (such as PMS data).

Do you want to know if and how you can apply the User Interface of Unknown Provenance process? What is your specific case? Comment on this post or get in touch via our contact form. We look forward to hearing from you.